It’s no secret my mind has been unreliable. A few months ago, I tried to die. I didn’t.

Now I spend hours on hold, listening to a flute rendered in MIDI, waiting for a stranger to tell me whether I still exist in the system. One bill, one prescription, one wrong tone with an insurance rep can decide whether you’re treated or forgotten. Getting help in America requires stamina, unemployment, and the ability to sound both desperate and polite.

That morning, I made breakfast. I hadn’t eaten in days. The smell of food made me nauseous, but I liked what hunger did to my face—the clean lines, the illusion of control. I cracked farmers’ eggs, added herbs, used expensive salt. I stared at the plate. You have to eat it, I said. Eat it. Then I screamed. Then I wept.

I scraped the food into the trash and lay on the couch until the light changed. I wasn’t planning to die that day. I sent memes to friends, wrote goodbye letters “for fun,” mostly jokes. Then I took every pill I had and drank a liter of wine. I wore a nice outfit, because why not. I remember crawling to the bathroom, throwing up without wanting to.

When I woke, I was sure I’d gone somewhere in between—purgatory, maybe, the holding cell for suicides. For two days I believed I was dead. On the third, I thought, Maybe I’m alive. Then I thought, Fuck.

My ex was in town. I told him not to come, then I said, Please. When he found me, I was translucent.

Verification as Medicine

The American health-care system doesn’t heal; it verifies. Every doorway—emergency room, intake form, crisis line—demands confession. You’re not treated until you’ve told the story correctly, in the right tone, with enough proof. I thought if I told it beautifully, I’d be believed. I wasn’t. Not until they saw my BMI. The doctor said my body had begun to cannibalize its own organs.

Every appointment begins with paperwork, ends with paperwork, and in between, there’s waiting—not for medicine, but for validation. Each phone call is an audition for care. Say too much, you sound unstable. Say too little, you sound fine. The system wants you distressed, but not dramatic. It rewards those who can narrate their pain professionally.

The Machinery of Casework

Caseworkers move through the system like people you meet at a party when you’re drunk. You learn their names, then forget them. Each handles a caseload the size of a small town—sixty, eighty, sometimes more—housing, addiction, eviction, despair. When one burns out, your file is forwarded to someone new. A new name, a new promise to “follow up.” You start over: childhood, diagnosis, suicide attempt, rent due next week. You learn to make it efficient, to use the words that trigger sympathy. You become your own stenographer.

Surveys of public social-service agencies show staggering turnover—30 to 40 percent a year—and caseloads that double recommended limits. “You can’t build trust,” one worker told me. “You’re just moving bodies through intake.”

Phantom Help

The system excels at simulation. You’re never quite abandoned, you’re almost helped. A voicemail promises a callback. A new intake appointment opens three weeks from now. The portal says pending review. Hope dangles like an IV drip—visible, humming, but never entering the vein.

Phantom help is the bureaucracy’s most elegant trick. It mimics progress: the auto-reply, the provisional approval, the cheerful reminder that your case is still active. Each gesture is a facsimile of care, engineered to keep you waiting. A form processed feels like a victory. A voicemail returned feels like love.

The Poverty Trap

Disability programs follow a similar moral math. Keep more than two thousand dollars in savings and you’re too rich for help. For Social Security Disability Insurance, you wait at least five months before the first payment, and your condition must be expected to last a year. In practice, approvals can take far longer, and many applicants reapply multiple times before success.

Section 8 housing goes further. Waitlists are often closed for years and reopen only briefly; most agencies give priority to people already experiencing homelessness. Prevention doesn’t compute. Only collapse counts as need.

Mental-health coverage is its own mirage. Therapists who take insurance are booked months out or have quit. The one I finally saw had never heard of complex PTSD. She asked me to explain it. I sent her The Body Keeps the Score. She thanked me for the reading material.

Every interaction produces paper—intake forms, progress notes, treatment plans—but not necessarily care. The file thickens; the person thins. Compliance appears on every line: the patient followed orders. It never asks whether the orders made sense.

The Big Beautiful Bill

Then comes the Big Beautiful Bill—officially, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Behind the branding lies arithmetic: roughly $900 billion cut from Medicaid over ten years, with non-partisan estimates projecting 10 to 11 million more uninsured by 2034, including about 7.5 million losing Medicaid coverage. Federal food assistance shrinks by nearly $180 billion; housing and social-service grants by $35 billion.

The language in Washington calls this streamlining. On the ground, it means fewer approvals, longer waits, vanished caseworkers. During the pandemic “unwinding,” millions lost Medicaid for paperwork errors rather than ineligibility—a preview of what’s to come.

When the letters arrive—the pastel envelopes stamped Statement of Benefits—they read like verdicts. Every test, every scan, every minute you were too weak to say no adds up to a number that could have been a down payment. For those already in need, it isn’t just a bill; it’s proof of failure, an invoice for surviving.

This, the bill insists, is what it costs to stay alive in America.

If a friend sends grocery money through an app, Social Security can treat it as unearned income; report it, and your SSI may shrink. The system assumes deceit. Prevention is punished more than collapse.

The Epidemic of the Almost Okay

Most of my friends hover just above the poverty line—working part-time or freelance, uninsured or underinsured, one medical bill from ruin. We are the “almost okay” generation: not destitute enough for help, not secure enough to rest. We borrow money, split rent, and pray our teeth hold out another year.

The cruelty is subtle. America doesn’t throw you out all at once. It lets you slip—paperwork by paperwork, denial by denial.

It teaches you to live in the waiting room.

The System’s Mercy

Sometimes I think the real religion of this country isn’t Christianity or capitalism—it’s bureaucracy. The triad of faith here is paperwork, process, and psychics. We confess. We wait. We are judged. The clerical class lives on, dressed in scrubs and headsets, reciting from scripts that begin with How are you feeling today? and end with Is there anything else I can help you with?

The system’s mercy arrives in the form of hold music. The human kind comes elsewhere.

Moon Goddess

The psychic was an older Black woman named Moon Goddess. We met on FaceTime. She cried when I told her what had happened. Her son had been murdered; her daughter, devoutly Christian, won’t speak to her because of the work she does. She told me tears were sacred—that every time I cried, I was anointing myself. She pulled cards and said, You’re going to be fine, baby. As we wept together, she said we were blessing each other.

The Slow Work of Staying

Lately I’ve been getting help. Slowly. Bureaucratically. The kind that comes in letters, forms, and calls placed on hold. I’ve gained the weight back. Food no longer feels like a test. I eat plums over the sink. I rap stupid things over the hold music. Sometimes I laugh at the forms—the small absurdities, the boxes that never quite fit, the question of whether to list my Xanax dealer as my emergency contact.

My savings thin. The rejections arrive like junk mail. I try not to take them personally. I tell myself things will work out, and if they don’t, there’s always another person on the line.

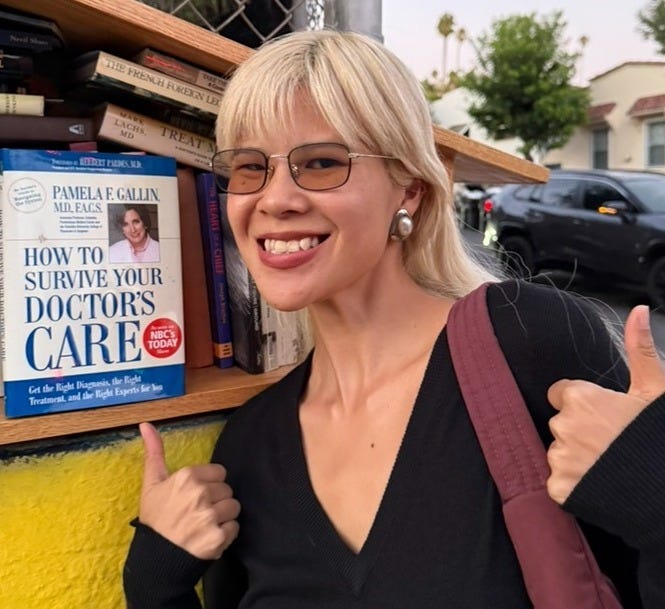

The air smells of jasmine—Los Angeles’s unofficial signature scent. It drifts overhead, then settles, so the sweetness falls on you like snow. The other day, I found a fig on the ground, soft and bursting in the heat. I ate it standing there on the curb.

For now, that will do.

If this essay moved you, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Writing these pieces takes time, care, and stability — the very things the system makes hard to afford.